The Early Christians Give Us the Signs of the Christian Life: Broken Bread & Lives Poured Out

The Early Christians Give Us the Signs of the Christian Life: Broken Bread & Lives Poured Out

In July of A.D. 64, during the tenth year of Nero’s reign, a great fire consumed much of the city of Rome. The fire raged out of control for seven days—and then it started again, mysteriously, a day later. Many in Rome knew that Nero had been eager to do some urban redevelopment. He had a plan that included an opulent golden palace for himself. The problem was that so many buildings were standing in his way—many of them teeming wooden tenements housing Rome’s poor and working class.

Convenient Fire

The fire seemed too convenient for Nero’s purposes—and his delight in watching the blaze didn’t relieve anybody’s suspicions. If he didn’t exactly fiddle while Rome burned, he at least recited his poems. Nero needed a scapegoat, and an upstart religious cult, Jewish in origin and with foreign associations, served his purposes well. Nero, who was a perverse expert at human torment, had some of its members tortured till they were so mad they would confess to any crime. Once they had confessed, he had others arrested.

He must have known, however, that the charges would not hold up. So he condemned them not for arson, or treason, or conspiracy, but for “hatred of humanity.”

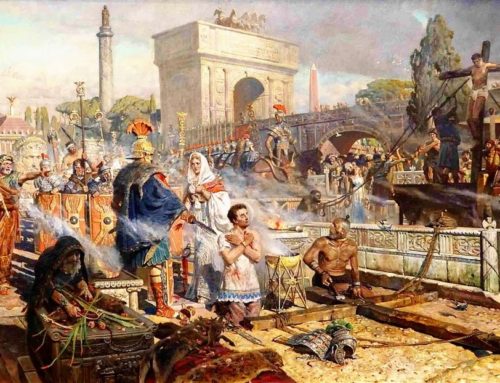

To amuse the people, he arranged for their execution to be a spectacle, entertainment on a grand scale. The Roman historian Tacitus (who had contempt for the religion, but greater contempt for Nero) describes in gruesome detail the tortures that took place amid a party in Nero’s gardens.

Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames. These served to illuminate the night when daylight failed. Nero had thrown open the gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or drove about in a chariot. Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being punished.

That is all we know about the first Roman martyrs. We know none of their names. Tacitus doesn’t tell us why they were willing to die this way rather than renounce their faith. Yet this should be an important question for us to consider. Why did the martyrs do this? What prepared them to face death so bravely? To what exactly did they bear witness with their death?

Let us begin with the witness we know best and ask ourselves: How can we spot a Christian today? What are the unmistakable signs that tell us we’re with a fellow believer?

Christian Signs

In the first generation of the Church, there were several unmistakable signs. St. Luke tells us that the first Christians, one and all, “devoted themselves to the teaching of the apostles and to the communion ( koinonia), to the breaking of the bread and to the prayers” (Acts 2:42). The teaching of the apostles, the communion, the breaking of the bread, and the prayers.

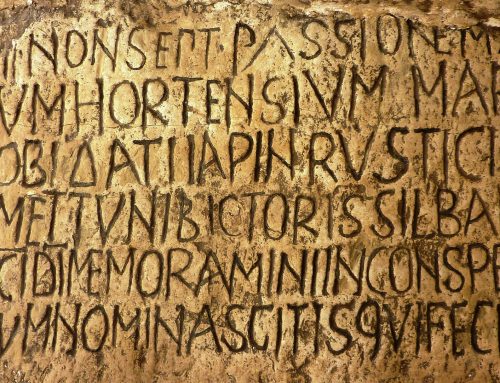

This is a precious snapshot, because we do not know as much about those first Christians as we would like to know. They were a small group, not especially wealthy, without social or political status, and often operating underground. What’s more, over the next 275 years, imperial and local governments tried fairly regularly to wipe out all traces of Christianity—destroying not only the Christians’ bodies, but their books and their possessions as well. So what we have left are the handful of documents that survived—mostly sermons, letters, and liturgies—as well as a few other scraps of parchment or painted wood, and the shards of pottery that the desert sands have preserved for us.

Yet what we see in those surviving documents and what we find in the archeological digs confirm all that we learn in the Acts of the Apostles, especially in one small detail: The first Christians “devoted themselves to the apostolic teaching, to the communion, and to the breaking of the bread and the prayers.” One phrase especially—the breaking of the bread—recurs in many of the scraps we have from those first centuries, and it always refers to the Eucharistic Liturgy, the Lord’s Supper.

Our first Christian ancestors devoted themselves to the Eucharist, and that is perhaps the most important way they showed themselves to be Christians. No Christian practice is so well attested from those early years. No doctrine is so systematically worked out as the doctrine of the Eucharist.

It was when they gathered for the Eucharist that all this—their common life, their charity, their fidelity to the teaching of the apostles—happened most clearly, directly, intensely. They experienced fellowship with each other and together heard the apostles’ teaching, and they broke the bread in the accustomed way, as they said the customary prayers.

So it was in the newborn Church. The Church took its identity from its unity in belief and charity, which was sustained by the Eucharist.

A Eucharist Everywhere

Christianity spread rapidly through the Roman Empire. One modern sociologist estimates that, in the centuries that concern us here, the Church grew at a rate of forty percent per decade. By the middle of the fourth century, there were 33 million Christians in an empire of 60 million people.

That meant that the Eucharist was celebrated everywhere. And the fact that it was celebrated everywhere was itself a favorite theme of the earliest church fathers. Justin the Martyr commented in the Dialogue with Trypho that, by the year 150, “There is not one single race of men . . . among whom prayers and Eucharist are not offered through the name of the crucified Jesus.”

The ancient Fathers commonly applied the Old Testament prophecy of Malachi to the liturgy: “from the rising of the sun to its setting my name is great among the nations, and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure offering.” Those lines found their way into many Eucharistic prayers, where they remain even to this day. (They appear, for example, in the third Eucharistic prayer in the Roman Missal: “so that from east to west a perfect offering may be made to the glory of your name.”)

As the Church moved outward from Jerusalem, this is what believers did. They offered the Eucharist. The early histories tell us that the first thing the Apostle Jude did when he established the Church in the city of Edessa was to ordain priests and to teach them to celebrate the Eucharist.

This is what the early Church was about. Everything that was good in Christian life flowed naturally and supernaturally from that one great Eucharistic reality: from the Christians’ sacramental experience of fellowship and communion, of the teaching of the apostles, of the breaking of the bread, and of the prayers.

Real Martyrdom

But there was another dominant reality in the ancient Church. It is something that appears just as often in the archeological record and in the paper trail of the early Christians. That something is martyrdom. Persecution.

Martyrdom occupied the attention of the first Christians because it was always a real possibility. Shortly after Christianity arrived in the city of Rome, the emperor Nero discovered that Christians could provide an almost unlimited supply of victims for his circus spectacles. The emperors needed to keep the people amused, and one way to do so was by giving them spectacularly violent and bloody entertainments.

The Christians’ morality made them none too popular with their neighbors anyway, so the citizens were more than willing to cheer as the Christians were doused with pitch and set on fire, or sent into the ring to battle hungry wild animals or armed gladiators. It was all in a day’s fun in ancient Rome. Over time, Nero’s perverted whims settled into laws and legal precedents, as later emperors issued further rulings on the Christian problem. Outside the law, mob violence against Christians was fairly common and rarely punished.

The Christians applied a certain term to their co-religionists who were made victims of persecution. They called them “martyrs”—which means, literally, witnesses in a court of law. And to the martyrs they accorded a reverence matched only by their reverence for the Eucharist.

In fact, the early Christians used the same language to describe martyrdom as they used to describe the Eucharist. We see this in the New Testament Book of Revelation, when John describes his vision of heaven. There, he saw “under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the witness they had borne.” There, under the altar of sacrifice, were the martyrs, the witnesses.

That image brings it all together. For, in those first generations of the Church, the most common phrase used to describe the Eucharist was “the sacrifice.” Both the Didache and St. Ignatius refer to it as “ the sacrifice.” And yet martyrdom, too, was the sacrifice.

God’s Wheat Ground

And so, in A.D. 107, when Ignatius described his own impending execution, he imagined it in Eucharistic terms. He said he was like the wine at the offertory. He wrote to the Romans: “Grant me nothing more than that I be poured out to God, while an altar is still ready.” Later in the same letter he wrote: “Let me be food for the wild beasts, through whom I can reach God. I am God’s wheat, ground fine by the lion’s teeth to be made purest bread for Christ.” Ignatius is bread, and he is wine; his martyrdom is a sacrifice. It is, in a sense, a eucharist.

Ignatius’s good friend Polycarp also died a martyr’s death. Polycarp was bishop of Smyrna, and had been converted by the Apostle John himself. His secretary described the bishop’s martyrdom, once again, as a kind of eucharist. Polycarp’s final words are a long prayer of thanksgiving that echoes the great eucharistic prayers of the ancient world and today. It includes an invocation of the Holy Spirit, a doxology of the Trinity, and a great Amen at the end.

When the flames reached the body of the old bishop, his secretary tells us that the pyre gave off not the odor of burning flesh but the aroma of baking bread. In yet another martyrdom, then, we find a pure offering of bread—a eucharist.

The Eucharistic images in Ignatius and Polycarp echo again in the future writings and histories of the martyrs. Even in the court transcripts, presumably taken down by pagan Romans, the Christians reply to the charges against them with lines from the liturgy. They lift up their hearts. And when they are sentenced, they say Deo gratias—thanks be to God.

The story of the martyr Pionius proceeds in the words, verbatim, of the eucharistic prayer: “and looking up to heaven he gave thanks to God.” The Greek word for “thanks” there is eucharistesas. So we might read it as, “Looking up to heaven, he offered the Eucharist to God,” even as the flames consumed him. In a similar way, the priest Irenaeus cried out, in the midst of torture, “With my endurance I am even now offering sacrifice to my God to whom I have always offered sacrifice.”

So pervasive is this eucharistic language in the early Church’s account of martyrdom that one of the great scholars of Christian antiquity, Robin Darling Young of Notre Dame, has spoken of the ancient Church having two liturgies: the private liturgy of the Eucharist and the public liturgy of martyrdom.

Loving Eucharist

But what is it about martyrdom that makes it like the Eucharist? Well, what has Jesus done in the Eucharist? He has given himself to us, and he has held nothing back. He gives us his body, blood, soul, and divinity. He gives himself to us as food. And that is love: the total gift of self. That is the very love the martyrs wanted to emulate. Jesus had given himself entirely for them. They wanted to give themselves entirely for him—everything they had, holding nothing back. If Jesus would become bread for them, they would allow the lions to make them finest wheat for Jesus.

So: Martyrdom was a total gift of self. The Eucharist was a total gift of self. In the Eucharist, Jesus gave himself to us. In martyrdom, we give ourselves back to him.

But there’s a problem here. Very few of the ancient Christians died for the faith. What about the rest? What was their gift? How did they live the Eucharist?

Not long after Christianity was legalized by Constantine, St. Jerome noted that some believers were already growing nostalgic for the good old days of the martyrs. But Jerome stopped such fantasies in their tracks. He told his congregation, “Let’s not think that there is martyrdom only in the shedding of blood. There is always martyrdom.”

There is always martyrdom. For most of the early Christians, the martyrdom came not with lions or fire or the rack or the sword. It came not at the hands of a mob or a gladiator. For most of the early Christians, “martyrdom” consisted in a daily dying to self in imitation of Jesus Christ.

Jesus told them: “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself . . . daily.” So the Christians denied themselves, in imitation of Jesus. What did this mean, in practical terms? It meant that they would never eat lavishly as long as others were going hungry. They would never keep an opulent wardrobe while others dressed in rags. They would never hold back their testimony to the faith as long as any of their neighbors were living in sin or in ignorance of the love of Jesus Christ.

Whatever they had, these Christians gave. They gave of themselves—just as the martyrs gave themselves in the arena—just as Jesus Christ gave himself on the Cross—and just as Jesus Christ gave himself in the Eucharist.

In Christ, these Christians had come into a Holy Communion. In baptism, they were baptized into his death, into Christ’s own martyrdom. In the Eucharist, they became one with him, in the deepest, and closest, and most intimate bond possible. They were closer to Jesus than they were to their best friends, closer to him than they were to their spouses. They were closer to Jesus than they were to their own parents or their own children. He himself had promised them that they would live in him, and he would live in them.

This was, and is, the deepest truth of the faith. In Jesus Christ, we live as sons and daughters of the eternal Father—we share his own divine life. In Jesus Christ, we can call God our Father because God is eternally his Father. In the New Testament, St. Peter puts our Holy Communion in the most powerful terms: We have become partakers of the divine nature.

The Life the Martyrs Knew

And what is that nature? How does God live in eternity? What is the Trinity for us, besides a theological abstraction and a mathematical enigma?

John said it all: God is Love. God is self-giving, life-giving love. From all eternity, God the Father pours himself out in love for the Son. He holds nothing back. The Son returns that love to the Father with everything he has. He holds nothing back. And (as the Western tradition has understood it) the love that they share is the Holy Spirit.

This is the life the martyrs knew even at the moment of their death— especially at the moment of their death. But they themselves had been caught up into that life so long before and so many times. They themselves had been caught up into the life-giving love of Jesus Christ—the life-giving love of the Blessed Trinity—whenever they had gone to the Eucharist. Whenever they had received Holy Communion. Whenever they had joined with their brothers and sisters for the teaching of the apostles and the communion, the breaking of the bread and the prayers.

Jesus gave himself entirely to them, and they gave themselves in return. At every Eucharist, he gives himself entirely to us, and we give ourselves entirely in return. We say Amen—So be it!—I accept. And when we do that, we consent to the communion.

We need to know what we’re doing when we say “Amen.” The life of Christ is more than a warm, fuzzy feeling that everything (including me) is okay and everything (no matter what I do) will work out fine. It’s accepting his cross. It’s accepting our martyrdom. And in the words of Garrison Keillor: If you don’t want to go to Minneapolis, what are you doing on the train?

There is always martyrdom. St. Paul had signaled this in his Letter to the Romans, where he wrote: “I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.” Surely Paul’s words reached many future martyrs in Rome, where he himself would one day die by beheading.

But his words reached many others as well, men and women whose sacrifice would be something quiet and hidden and noticed only by God. It is the same St. Paul who referred to our bodies as “temples of the Holy Spirit.” Let’s not ever forget that, in the ancient world, temples were not mere shrines; they were places of sacrifice.

And so are we. Our bodies are places of sacrifice, and our lives are the offering on the altar. We ourselves are the Eucharist in motion.

The Look of Love

Our everyday life should be a voluntary sacrifice, voluntary self-giving, voluntary martyrdom. Listen to the traditional language about penance and reparation, mortification, fasting, pilgrimage, and almsgiving. It’s all about self-possession, self-denial, self-mastery. And all that is great. It is good to be disciplined, and self-denial is a means to achieving discipline. But discipline, too, is a means and not an end in itself. Why do we want to possess ourselves?

Jesus shows us why. We possess ourselves in order to give ourselves away—just like Jesus, just like the martyrs. Only then can we become truly ourselves. For we are made in God’s image, and God is life-giving love, whose human life was a self-giving sacrifice. The Eucharist is that sacrifice, and all our lives must be placed upon the altar, all our lives must be taken up into the Eucharist.

Remember the question I asked earlier: How can we spot a Christian today? The same way we could have spotted them on the streets of first-century Rome: by their Eucharistic lives. When we give ourselves without holding back, we are living like the early Christians. We are living like the martyrs. We are living like the Most Blessed Trinity in heaven.

St. Irenaeus put it well, around the year A.D. 190: “Our way of thinking is attuned to the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn confirms our way of thinking.”

What does it look like in the day-to-day? It looks like a mother staying up all night with a sick child—or a grandmother up late with the child so that her daughter can get some sleep. It looks like a husband working overtime at a job he doesn’t particularly enjoy, so that his family can know a better life. It looks like a family keeping vigil by a deathbed. It looks like the dying man who musters a smile for his loved ones.

It looks like the young couple who give up life in suburbia to head off to the mission field. It looks like the religious sister who has renounced family and liberty in order to give herself entirely to Jesus Christ and his Church. It looks like a pastor, who must serve as father and teacher and psychologist and sage and business manager—and can’t find enough hours in the day.

That’s the total gift of self. It’s what the early Christians knew. And it’s what we must come to know for ourselves, if we want to become ourselves—if we want to become what God made us to be. There’s no other way to be happy. It’s all there in the Mass of the early Christians, and in the Eucharist we attend on Sunday, the Eucharist we live every day of our lives.

Mike Aquilina is vice president of the St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology (www.salvationhistory.com) and a general editor of The Catholic Vision of Love catechetical series.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.