Early Christian literature: The apostolic fathers

Christian literature began with the ‘Apostolic Fathers,’ whose writings reflect the way of life of the early Christians. The ‘Apologists’ wrote in defense of the faith and the third century saw the beginnings of theological writing in the strict sense.

1. The New Testament

The New Testament consists of twenty-seven books, all of them written in the second half of the first century. Four gospels cover the life and teachings of our Lord Jesus Christ; the Acts of the Apostles — written by St Luke — are also an historical record, dealing with the life of the early church of Jerusalem and going on to describe the activities of St Paul the Apostle up to his arrival at Rome to appear before the judgment seat of Caesar.

A second group of books — didactic in character — consists of fourteen letters of St Paul and seven ‘catholic‘ epistles — two by St Peter, three by John, one by James and one by Jude. A prophetic book — the Book of Revelation or the Apocalypse of St John — concludes the series of inspired books which contain the divine revelation of the New Testament. This inspired scripture is followed by early Christian literature.

2. The Birth of Christian literature

Early Christian writing reflects the way of life of the early Church. As time went by, the growing Church had to face difficulties from within and without, and once it achieved a certain maturity it felt the need to develop a systematic exposition of the content of the faith. All this development occurred during the first three centuries of our era, before Emperor Constantine granted freedom of religion. The literary texts which have come down to us allow us to plot the various stages of this historical development.

3. The Apostolic Fathers

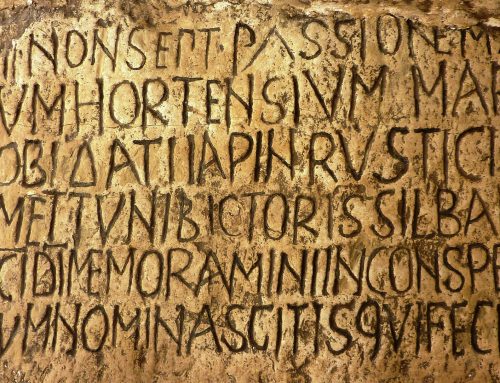

The oldest of these writings came from a number of Greek writers, of the first and second centuries, known by the name of the ‘Apostolic Fathers.’ This title describes their special characteristics: their antiquity (some of these works were, probably, written before St John‘s Gospel) and the close links between these writers and the Apostles (they may be considered disciples of the Apostles). The writings of the Apostolic Fathers are pastoral in character and are addressed to a Christian readership.

The most outstanding texts in this first group of Christian writings are the Didache (the oldest known account of church discipline), the letter of St Clement to the Corinthians, which we have already mentioned; the seven letters of St Ignatius of Antioch to other churches, written on his journey to Rome, where he would suffer martyrdom; and another letter, by St Polycarp of Smyrna. The Shepherd of Hennas, which has importance for tracing the history of penitential practice, also belongs to this group.

4. The Acts of the Martyrs

The early Church was the Church of the martyrs. The faithful were keen to have accounts of the heroism of those who had given their lives for the Christian faith. Undoubtedly their curiosity led to the concocting of legendary accounts, which have little value as history; but there are quite a number of documents about martyrs which carry every guarantee of being accurate.

In many cases martyrdom was preceded by a judicial process in which notaries recorded magistrates’ questions, the martyrs’ replies and the sentence condemning them to death. Sometimes the Christians managed to obtain transcripts of these court documents: for example, this happened in the cases of St Justin, who was tried in Rome (c. 165), and of St Cyprian of Carthage (c. 258). Accounts of martyrdoms written by Christian eye-witnesses have the same sort of documentary value as these court acta; they consisted of a few touching pages which used to be read out in the churches on the anniversary of the martyr’s death.

5. Christian Apologetics

In the second century a new kind of literature grew up which shows the struggles of Christians against enemies from inside and outside the Church. The defence of the faith against heresy gave rise to a good number of anti-heretical writings. The most outstanding is St Irenaeus of Lyons‘ treatise Against Heresies, which we have already referred to and which is a refutation of gnostic teachings. Irenaeus placed key emphasis on the tradition conserved by the bishops, the successors of the Apostles, and especially the tradition of the Roman church, the teacher of the faith adorned with a special primacy over all the other churches.

The main objective of the ‘Apologists’ was to indicate Christian truth, and their writings were directed at readers outside the Church. Some of these apologetic works, addressed to Jews, refuted Jewish criticism of Christianity, arguing from the Old Testament to show that Jesus was the messiah foretold by the prophets, that the Church was the new Israel and that Christianity was the fullness of the law. A notable example of this type is the Dialogue with Trypho, written by St Justin Martyr around the year 150. But generally these writings were addressed to the typical pagan hostile to Christianity.

The Apologists were a group of writers who took it upon themselves to defend Christianity against the Gentile world. In keeping with this purpose, they addressed themselves to people in authority — emperors, magistrates — or to the Roman people in general. The content of their writings was dictated by the kind of accusations being levelled against Christians at any particular time.

To deal with accusations that Christians were guilty of all sorts of crimes, the Apologists replied by giving an enactment of the real way of life of Christ’s disciples. The Letter to Diognetus (which may have been the apologia presented by Quadrants to Emperor Hadrian) presents this witness to the Christian way of life as the best proof of the falsity of anti-Christian calumnies. Indeed, the author goes on, the conduct of Christians is so admirable that the only explanation can lie in the greatness of their ideals: ‘they love all men, yet all men persecute them; they are not known, yet they are condemned; they are put to death, yet this gives them life; they are poor, yet they enrich many; they lack everything, yet they have everything in abundance; they, are dishonoured, yet this very dishonour glorifies them.’

Christians were accused of being enemies of mankind and bad citizens of the empire. The Apologists reacted vigorously against this sort of attack: Christians, they wrote, bring a beneficial influence to bear on society: ‘what the soul is in the body, so are the Christians in the world’, was how the Letter to Diognetus argued, and Origen, in his reply to. Celsus, reaffirmed that ‘the men of God [the Christians] are the salt which binds together the societies of the earth.’ As far as the empire was concerned, the Apologists of the second century claimed that the Christians were completely loyal: they were exact in performing their duties as citizens and they offered to emperors the very best they had to offer — their prayers: ‘We pray at all times for the emperors,’ Tertullian wrote in his Apologeticum, ‘that they may have long life, and we ask for benign government, the security of the state, a strong army, a faithful senate, an honorable people, peace in the world and whatever emperors and subjects may desire.’

The Christians still faced opposition from intellectuals who saw little of intellectual value in Christianity. The Apologists‘ reply was that Christian teaching was a knowledge infinitely superior to Greek philosophy, for it held the complete truth. Around the year 200, some writers who had provided an intellectual defence of Christianity began to produce non-polemical literature, of a kind demanded by the growing maturity of the Church: expositions of the whole body of Christian teaching, to be used to educate the very many converts who began to come from more educated sectors of society. This was how the science of theology began.

If we had to assign a location to the origin of this science we would have to answer, unhesitatingly, Alexandria. In that cosmopolitan city, the focus of hellenistic culture, there grew up a famous theological school which, at the beginning of the third century, achieved extraordinary prestige under the leadership of Clement, a convert, whose great culture enabled him to expound the teaching of the faith within a structured, intellectual framework. The intellectual atmosphere of the Egyptian metropolis impressed its features on this Christian school — a preference for Platonic philosophy and the use of the allegorical method in biblical exegesis, in search of the deepest spiritual meaning of sacred scripture. All Alexandrian theologians have these characteristics.

Origen, the successor of Clement at Alexandria, brought this school to the peak of its prestige. Origen was an extraordinary person: a confessor of the faith, a most prolific writer, his intellectual reputation spread throughout the empire, to the extent that the mother of Emperor Alexander Severus sought to hear him lecture. He worked at an amazing pace, first in Alexandria and then in Caesarea in Palestine. Through St Jerome we know the names of eight hundred of the two thousand works he composed. His most ambitious undertaking, which took him his lifetime to complete, was the Hexapla, a sextuple version of sacred scripture aimed at establishing a critical edition of the Old Testament.

Source: José Orlandis (A Short History of the Catholic Church, 2001)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.