The Church continues to make Christ present in human history. In the history of the Church, we find the divine and the human closely intertwined.

The Church continues to make Christ present in human history. In the history of the Church, we find the divine and the human closely intertwined.

In the first century Christianity began to spread under the guidance of St. Peter and the Apostles, and afterwards of their successors. The number of Christ’s followers steadily increased, above all within the confines of the Roman Empire. At the beginning of the fourth century, Christians made up approximately 15% of the population of the Empire, concentrated in the cities and in the Eastern portion of the Roman state. The new religion also spread to Armenia, Arabia, Ethiopia, Persia, and India, outside the Empire’s boundaries.

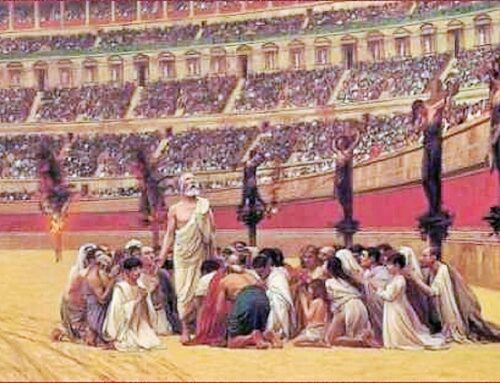

The Roman political power saw in Christianity a threat to its authority, since this new religion claimed a sphere of freedom of conscience vis-à-vis the state. Christ’s followers, consequently, had to endure repeated persecutions that brought many of them to martyrdom. The last and cruelest of these took place at the beginning of the fourth century, under the Emperors Diocletian and Galerius.

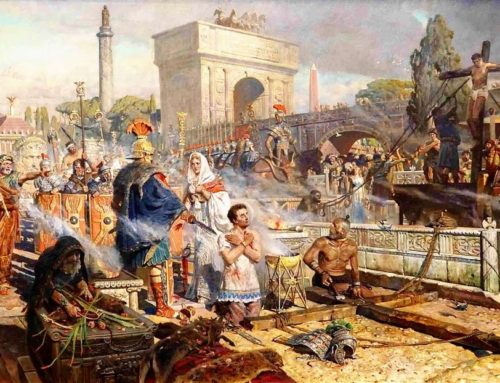

In the year 313, the Emperor Constantine I, who was favorable to the new religion, granted Christians freedom to profess their faith and initiated a very benevolent policy towards them. Under the Emperor Theodosius I (379-395), Christianity became the official religion of the Roman. Empire, and by the end of the fourth century, Christians were now a majority of the population.

In the fourth century, the Church also had to face a serious crisis: Arianism. Arius, a priest from Alexandria, Egypt, held heterodox opinions that denied the divinity of the Son (as well as of the Holy Spirit). He viewed the Second Person as the first among all creatures, although superior to them. This doctrinal crisis, aggravated by frequent interventions by the emperors, shook the Church for over 60 years. It was finally overcome thanks to the first two Ecumenical Councils: the First Council of Nicaea (325) and the First Council of Constantinople (381). In them, Arianism was condemned, and the divinity of the Son ( consubstantialis Patri , homoousios in Greek) was solemnly proclaimed, as well as that of the Holy Spirit. The true faith was set forth in the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Symbol or Creed. Arianism survived until the seventh century because Arian missionaries succeeded in converting to their beliefs many Germans, who only gradually accepted the Catholic teaching.

In the fifth century, two Christological heresies had the positive effect of obliging the Church to consider more thoroughly the dogma of the Incarnation and to formulate it with greater precision. The first of these was Nestorianism, which, in practice, claimed the existence of two persons in Christ, along with the two natures. It was condemned at the Council of Ephesus (431), which reaffirmed the oneness of the person of Christ. From Nestorianism stem the Eastern Syrian and Malabar Churches, which are still separated from Rome. The other heresy was Monophysitism, which held, in practice, that only one nature existed in Christ, the divine one. The Council of Chalcedon (451) condemned Monphysitism and stated that there are two natures in Christ, one divine and the other human, united in the Person of the Word without confusion or change, and without division or separation. The four adverbs used by Chalcedon were inconfuse , immutabiliter , indivise , inseparabiliter . From the Monophysites came the Coptic, Western Syrian, Armenian and Ethiopian Churches that are separated from the Catholic Church.

The first centuries of the history of Christianity witnessed a great flowering of Christian literature—homiletic and theological, as well as spiritual—found in the works of the Fathers of the Church. These works were very important in establishing Sacred Tradition. The most important figures were, in the West, Irenaeus of Lyon, St. Hilary de Poitiers, St. Ambrose of Milan, St. Jerome and St. Augustine; and in the East, St. Athanasius, St. Basil, St. Gregory Nazianzus, St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. John Chrysostom, St. Cyril of Alexandria and St. Cyril of Jerusalem.

OpusDei.uk

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.