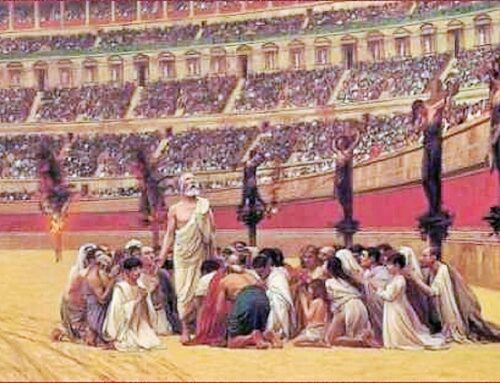

The Church continues to make Christ present in human history. In the history of the Church, we find the divine and the human closely intertwined.

The Church continues to make Christ present in human history. In the history of the Church, we find the divine and the human closely intertwined.

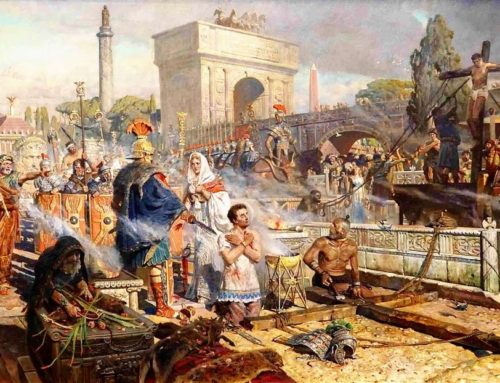

The Modern Age opens with the arrival of Christopher Columbus in America, an event which, along with the explorations in Africa and Asia, began the European colonization of other regions in the world. The Church took advantage of this historical event to spread the Gospel in continents outside Europe. Missions arose in the French colonies of Canada and Louisiana in North America, in Spanish America, in Portuguese Brazil, in the Congo, India, Indochina, China, Japan and the Philippines. To coordinate these endeavors for spreading the faith, the Holy See in 1622 instituted the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide .

Meanwhile, the Church was entering the grave crisis of the “Reformation” initiated by Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, and John Calvin (all founders of different denominations of Protestantism), along with the schism provoked by Henry VIII, king of

England (Anglicanism). This resulted in the separation from the Church of a large part of the world: Scandinavia, Estonia and Lithuania, part of Germany, Holland, half of Switzerland, Scotland, England, besides their respective colonial territories already possessed or subsequently conquered (Canada, North America, the Antilles, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand). The Protestant Reformation had the damaging effect of breaking up the long-standing religious unity in the western Christian world, and caused the various states to become confessional. It thereby brought about the social, political and cultural division of Europe and some of its dependent regions into two camps, Catholic and Protestant. This situation crystallized in the formula, cuius regio, eius et religio , according to which the subjects of each region were obliged to follow the religion of their respective rulers. Confrontation between these two worlds led to the wars of religion, which especially affected France, the German territories, England, Scotland, and Ireland. Hostilities in this conflict ended only with the Peace of Westphalia (1648) on the continent, and with the capitulation of Limerick (1692) in the British Isles.

Although deeply wounded by the defection of so many people in so few decades, the Catholic Church was able to draw upon unsuspected interior reserves to react and begin carrying out an authentic reform. This historical process came to be known as the Counter-Reformation., whose high point was the Council of Trent (1545-1563). There some dogmatic truths were clearly proclaimed that had been placed in doubt by the Protestants, such as the canon of Scripture, the sacraments, justification, and original sin. Disciplinary measures were also taken that strengthened and consolidated the Church, for example, the establishment of seminaries, and the obligation of residency in the diocese for bishops. The efforts of the Counter-Reformation were assisted by many religious orders in the sixteenth century. These were initiatives of reform by the mendicant Capuchins and Discalced Carmelites, and institutes of regular clerics, Jesuits, Theatines, Barnabites, etc. The Church thus emerged from the crisis deeply renewed and strengthened, and was able to make up for the loss of some European regions with a truly universal growth, thanks to the work in the missions.

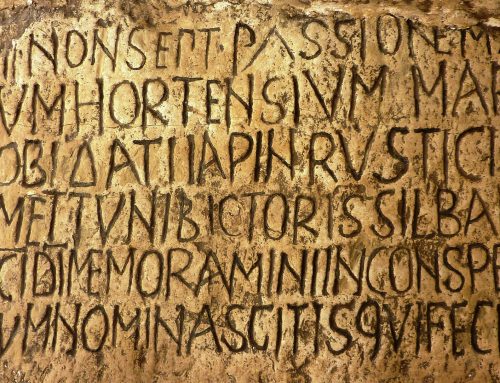

In the eighteenth century, the Church had to fight two enemies: “royalism” and the enlightenment. The first was closely tied to the development of absolute monarchy. Supported by the organization of a modern bureaucracy, the European sovereigns established a system of total, autocratic power, eliminating the barriers that had formerly been present, namely, the institutions of medieval origin such as the feudal system, ecclesiastical privileges, the rights of cities, etc. In this effort to centralize power, the Catholic monarchs often infringed on ecclesiastical jurisdiction in striving to create a Church submissive to the power of the king. This process took on different names, depending on the particular country concerned: “royalism” in Portugal and Spain, Galicanism in France, Josephism in the Hapsburg territories of Austria, Bohemia, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Croatia, Lombardy, Tuscany, Belgium, and “jurisdictionalism” in Naples and Para. It reached its zenith with the expulsion of the Jesuits by many governments, and the hostile pressure exerted on the papacy to suppress the order, as in fact happened in 1773

The other enemy the Church had to contend with in the eighteenth century was the enlightenment, a movement that was above all philosophical, and that was very popular among the ruling class. Underlying it was a cultural current that exalted reason and nature, while fostering an indiscriminant criticism of tradition. It combined many complex strands, with a strong materialistic tendency, a naive exaltation of science, rejection of revealed religion in the name of “deism” or incredulity, an unrealistic optimism regarding man’s natural goodness, an excessive anthropocentrism, a utopian confidence in human progress, a widespread hostility against the Catholic Church, a self-sufficient attitude and scorn of the past, and finally, a deeply rooted tendency to hold simplistic and “reductionist” views. It spawned many modern ideologies that restrict the vision of reality by eliminating supernatural revelation, the spirituality of man, and ultimately, any aspiration to seek the truth about the human person and God.

In the eighteenth century, the first Masonic Lodges were founded, with a tone and agenda that were often clearly anti-Catholic.

OpusDei.uk

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.