In the ancient lists of the Twelve he always comes before Matthew, whereas the name of the Apostle who precedes him varies; it may be Philip (cf. Mt 10: 3; Mk 3: 18; Lk 6: 14) or Thomas (cf. Acts 1: 13).

In the ancient lists of the Twelve he always comes before Matthew, whereas the name of the Apostle who precedes him varies; it may be Philip (cf. Mt 10: 3; Mk 3: 18; Lk 6: 14) or Thomas (cf. Acts 1: 13).

His name is clearly a patronymic, since it is formulated with an explicit reference to his father’s name. Indeed, it is probably a name with an Aramaic stamp, bar Talmay, which means precisely: “son of Talmay”.

We have no special information about Bartholomew; indeed, his name always and only appears in the lists of the Twelve mentioned above and is therefore never central to any narrative.

However, it has traditionally been identified with Nathanael: a name that means “God has given”.

This Nathanael came from Cana (cf. Jn 21: 2) and he may therefore have witnessed the great “sign” that Jesus worked in that place (cf. Jn 2: 1-11). It is likely that the identification of the two figures stems from the fact that Nathanael is placed in the scene of his calling, recounted in John’s Gospel, next to Philip, in other words, the place that Bartholomew occupies in the lists of the Apostles mentioned in the other Gospels.

Philip told this Nathanael that he had found “him of whom Moses in the law and also the prophets wrote, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph” (Jn 1: 45). As we know, Nathanael’s retort was rather strongly prejudiced: “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” (Jn 1: 46). In its own way, this form of protestation is important for us. Indeed, it makes us see that according to Judaic expectations the Messiah could not come from such an obscure village as, precisely, Nazareth (see also Jn 7: 42).

But at the same time Nathanael’s protest highlights God’s freedom, which baffles our expectations by causing him to be found in the very place where we least expect him. Moreover, we actually know that Jesus was not exclusively “from Nazareth” but was born in Bethlehem (cf. Mt 2: 1; Lk 2: 4) and came ultimately from Heaven, from the Father who is in Heaven.

Nathanael’s reaction suggests another thought to us: in our relationship with Jesus we must not be satisfied with words alone. In his answer, Philip offers Nathanael a meaningful invitation: “Come and see!” (Jn 1: 46). Our knowledge of Jesus needs above all a first-hand experience: someone else’s testimony is of course important, for normally the whole of our Christian life begins with the proclamation handed down to us by one or more witnesses.

However, we ourselves must then be personally involved in a close and deep relationship with Jesus; in a similar way, when the Samaritans had heard the testimony of their fellow citizen whom Jesus had met at Jacob’s well, they wanted to talk to him directly, and after this conversation they told the woman: “It is no longer because of your words that we believe, for we have heard for ourselves, and we know that this is indeed the Saviour of the world” (Jn 4: 42).

Returning to the scene of Nathanael’s vocation, the Evangelist tells us that when Jesus sees Nathanael approaching, he exclaims: “Behold, an Israelite indeed, in whom there is no guile!” (Jn 1: 47). This is praise reminiscent of the text of a Psalm: “Blessed is the man… in whose spirit there is no deceit” (32[31]: 2), but provokes the curiosity of Nathanael who answers in amazement: “How do you know me?” (Jn 1: 48).

Jesus’ reply cannot immediately be understood. He says: “Before Philip called you, when you were under the fig tree, I saw you” (Jn 1: 48). We do not know what had happened under this fig tree. It is obvious that it had to do with a decisive moment in Nathanael’s life.

His heart is moved by Jesus’ words, he feels understood and he understands: “This man knows everything about me, he knows and is familiar with the road of life; I can truly trust this man”. And so he answers with a clear and beautiful confession of faith: “Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!” (Jn 1: 49). In this confession is conveyed a first important step in the journey of attachment to Jesus.

Nathanael’s words shed light on a twofold, complementary aspect of Jesus’ identity: he is recognized both in his special relationship with God the Father, of whom he is the Only-begotten Son, and in his relationship with the People of Israel, of whom he is the declared King, precisely the description of the awaited Messiah. We must never lose sight of either of these two elements because if we only proclaim Jesus’ heavenly dimension, we risk making him an ethereal and evanescent being; and if, on the contrary, we recognize only his concrete place in history, we end by neglecting the divine dimension that properly qualifies him.

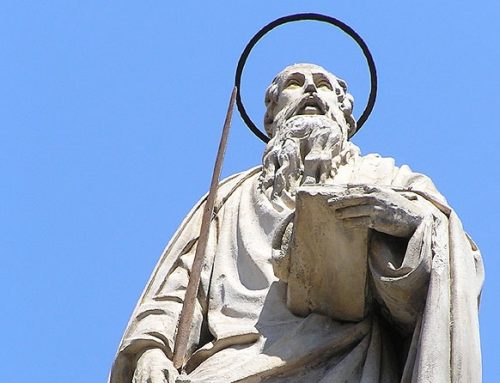

We have no precise information about Bartholomew-Nathanael’s subsequent apostolic activity. According to information handed down by Eusebius, the fourth-century historian, a certain Pantaenus is supposed to have discovered traces of Bartholomew’s presence even in India (cf. Hist. eccl. V, 10, 3).

In later tradition, as from the Middle Ages, the account of his death by flaying became very popular. Only think of the famous scene of the Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel in which Michelangelo painted St Bartholomew, who is holding his own skin in his left hand, on which the artist left his self-portrait.

St Bartholomew’s relics are venerated here in Rome in the Church dedicated to him on the Tiber Island, where they are said to have been brought by the German Emperor Otto III in the year 983.

To conclude, we can say that despite the scarcity of information about him, St Bartholomew stands before us to tell us that attachment to Jesus can also be lived and witnessed to without performing sensational deeds. Jesus himself, to whom each one of us is called to dedicate his or her own life and death, is and remains extraordinary.

Benedict XVI (General Audience 4 October 2006)

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.