An article on the historical reality of Jesus of Nazareth: “The preaching of the early Church always presented Jesus as the Son of God and the only Savior.”

An article on the historical reality of Jesus of Nazareth: “The preaching of the early Church always presented Jesus as the Son of God and the only Savior.”

At the beginning of the third millennium, a special interest in Jesus of Nazareth seems to have awakened in the world. Books written about him in recent years, although not always positive, have emphasized the timeliness and transcendence of the Son of God made man, and the attractiveness of his life. For in his communion with the Father, Jesus is present to us today. And what does Jesus bring, what does he give to the world? The answer is simple: God. [1]

“Stir up the fire of your faith. Christ is not a figure of the past. He is not a memory lost in history. He lives! As St. Paul says: Iesus Christus heri et hodie: ipse et in saecula!Jesus Christ is the same yesterday and today—yes, and forever!” [2]

The preaching of the early Church always presented Jesus as the Son of God and the only Savior. The proclamation of the Paschal Mystery brought with it a paradoxical announcement of humiliation and exaltation, of shame and triumph: We preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God . [3]

It was not easy for the first Christians to overcome the scandal of the Cross, the reality of the crucifixion and death of the Son of God himself. The Docetists and the Gnostics tried to deny that Jesus had a real body that could suffer, while Nestorius, two centuries later, claimed that there were two persons in Jesus, one human and the other divine.

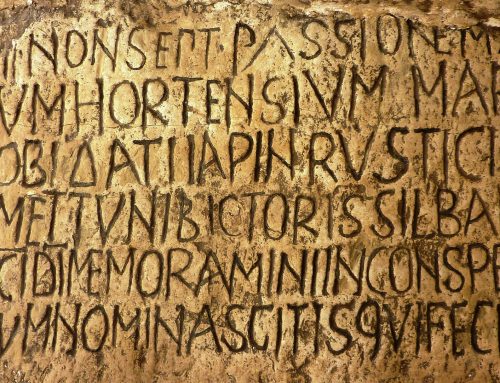

But the historical reality of Jesus of Nazareth does not escape any serious student. Although we do not have a large amount of extra-biblical accounts of him and his mission, these are sufficient to state without any doubt that he lived on earth. The testimony of Flavius Josephus, for example, is substantially accepted. In one of his books, this first-century Jewish historian refers to Jesus as “a wise man, if one can refer to him as a man; he carried out extraordinary deeds, being a teacher of men who accept the truth.” [4] Later, during the reign of Emperor Trajan, Pliny the Younger and Tacitus wrote about Jesus; and afterwards Suetonius, Hadrian’s secretary, did the same.

However, besides these references, the Gospels are “our principal source for the life and teaching of the Incarnate Word, our Savior.” [5] They provide us with a detailed picture of his personality. The Church’s tradition, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, has recognized in these writings an authentic and sure representation of the historical figure of our Lord, a figure who possesses a divine character.

The value of the Gospels as primary sources for knowing Jesus was not cast into doubt by Christians until the end of the eighteenth century. Several Protestant writers from that period attempted to analyze the Gospels with exclusively rationalistic criteria, eliminating the passages they considered unacceptable to “modern man,”that is, the miracles and prophecies, which can only be explained by an extraordinary divine intervention in history. This was the first attempt to study the Gospel texts outside of the Church’s tradition, setting aside faith in Christ’s divinity.

From that time on, a number of “lives of Jesus” appeared that presented Christ as one of many candidates claiming to be the Messiah. His life was seen as a failure: a person condemned to death by the Roman authorities, but who, it had to be admitted, did possess an undeniable moral authority. These attempts at an “historical” biography often ended up painting a portrait of the person writing it, rather than of Jesus Christ.

Later on, the advance of exegetical studies led to a strong reaction against this practice. The Gospels came to be seen as texts written with a sincere faith, but as distorting the facts, making it impossible to arrive at any certainty regarding what was being recounted. These studies thus fostered skepticism about the divinity of the historical figure of Christ. Nevertheless, as Benedict XVI points out in his book Jesus of Nazareth ,modern exegesis, in making use of new methodological insights that go beyond the limits of the historical-critical method, offers a theological interpretation of the Bible that is fully in accord with the faith. [6]

The truth proclaimed by the Church about the Son of God, who after twenty centuries continues to be a stumbling block for the intellect, presents us with a Person to whom we need to commit our own life through an act of faith. But not a purely “fiducial” or credulous faith—rather a faith that rests upon what God himself said and did in history, a faith that believes in the real life and deeds of the Son of God made man, and which finds in him the reason for its hope.

The importance of the historical reality of the Gospel message has been clear from the first moments of Christianity. As St. Paul said, if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain and your faith is in vain.[7]

The miracles and authority of Jesus

The Gospels tell us that Jesus worked miracles. The Old Testament also contained accounts of wonders carried out by prophets such as Elijah and Elisha, as well as those involving Moses and Joshua. Outside the context of the Bible, in ancient literature, both Jewish and Hellenistic, it was quite common to attribute wonderful deeds to the heroes of a story.

Those who try to deny the truth of Christ’s miracles—and all the other wonders recounted in Scripture—usually point to these stories in support of their claim that narratives of miraculous deeds imply a fictional literary genre, perhaps aimed at exalting an historical figure.

But the similarities quickly give way to deep differences, which point to the credibility and authenticity of the Gospel accounts. In the first place, Jesus’ miracles are surprising in their verisimilitude when compared to those found in other traditions. The evangelists do speak of wonders, but there is nothing exaggerated in the way they describe them. A blind man recovers his sight; a cripple begins to walk…. The very simplicity of the narrative makes it clear that it is not trying to exalt anyone. These narratives are devoid of any kind of ostentation, simply recording their subjects’ daily lives.

Our attention is also drawn to the authority with which Jesus carries out these deeds. The wonders recounted in rabbinical literature come about after long prayers. By contrast, Jesus works them by his own power, with a word or gesture, and the miracle almost always follows immediately.

Another unique characteristic is Jesus’ discretion: he rarely takes the initiative, and is reticent about having his miracles known, instructing those present not to tell anyone. The sacred text sometimes even states that he could not work any miracles[8] because he did not find the required spiritual dispositions in the people involved.

Finally, it is important to note that Christ’s miracles always have a meaning that transcends the mere physical effect. Our Lord does not pander to people’s thirst for the marvelous or to their curiosity. He seeks the conversion of a soul, to testify to his mission. Jesus makes it clear that his miracles are not simply wonder-working. To work them he demands faith in his Person, in the mission the Father has entrusted to him.

Thus we can conclude that the Evangelists sought to put historical facts within everyone’s reach, in order to stir up their faith. They bear witness to the reality that “everything in Jesus’ life was a sign of his mystery. His deeds, miracles, and words all revealed that ‘in him the whole fullness of deity dwells bodily.'” [9]

Hence the centrality, in Christian life, of St. Josemaria’s advice: “Capture the flavor of those moving scenes where the Master performs works that are both divine and human, and tells us, with human and divine touches, the wonderful story of his pardon for us and his enduring Love for his children. Those foretastes of Heaven are renewed today, for the Gospel is always true: we can feel, we can sense, we can even say we touch God’s protection with our own hands.” [10]

Jesus’ authority, nevertheless, is shown not only in his way of working miracles. It is seen still more clearly in the way he approaches the Law and tradition. He interprets these, showing their true depth, and corrects them. This is another distinguishing feature not found in any other testimony from that time. This originality, so clear in the teachings collected in the Gospels, can only be explained by the unique character of the Master, by his strong personality and doctrine.

His power over the Law is seen when we examine how he fulfilled it so faithfully. By that fulfillment, Christ revealed demands that reach right to the depths of the heart, transcending any trace of formalism.

It is clear that Jesus upheld the Law, but he interpreted it according to a new spirit. Thus, at the same time as he fulfilled it, he surpassed it. He brought new wine that rejected any compromise with the old wineskins. In addition, he did so as a legislator who speaks in his own name, going beyond Moses. What God had said through Moses was perfected by his only-begotten Son.

Jesus inaugurated a new era, that of the Kingdom announced by the prophets long ago. He destroyed the kingdom of Satan, casting out spirits with the finger of God.[11]The fact that Jesus was the Messiah could not have been invented by his disciples after Easter. The Gospel tradition contains too many solid and harmonious recollections of his public life for someone to claim that it is a posthumous invention, manufactured for the purposes of apologetics. Christ’s teachings are inseparable from the authority with which he proclaimed them.

Jesus’ Divinity in the Gospels

Just as some people try to deny the historicity of the miracles, it is sometimes said that the title “son of God” in the Gospels only indicates a certain special closeness of Jesus to God. Those making this claim usually point out that this title has various uses in texts from that era. It was applied to people of outstanding holiness, to the people of Israel, to the angels, to royalty, or to people with some special faculty. But when we consider the Gospel narratives, once again differences become evident that are only explicable if Christ’s divine nature is recognized.

Thus the Gospel according to St. Mark bears witness to the fact that Jesus’ personality transcends the merely human. Certainly, sometimes Jesus is called the son of God by those who are perhaps only using this phrase in the normal meaning that it then had, without recognizing its deeper implications.

But we also hear the voice of the Father himself at the Baptism and the Transfiguration testifying that Jesus is the Son of God. In the light of this declaration, we can appreciate in many other passages the real and unique character of Christ’s divine filiation. For example, Jesus presents himself as the “beloved son” in the parable of the murderous men who rent out the vineyard, and thus as a radically different figure from those sent earlier. He also shows a unique personal relationship of filiation and confidence with the Father when he calls him Abba , [12] Dad or “Papa.” (Mark’s is the only Gospel that contains this expression.) In this context it is interesting to see how the Evangelist’s faith in Jesus’ divinity is highlighted by the very first verse, the Gospel of Jesus Christ, the Son of God , [13] and by the centurion’s confession, near the end of the Gospel: Truly this man was the Son of God![14]

In St. Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus’ divine filiation is presented more frequently than in St. Mark. The title is proclaimed by people who are possessed, by the centurion, by those passing beneath the Cross at Calvary, by the priests, and by Peter and the disciples, especially after a miracle. Even more clearly than in St. Mark, we see that not all those who call him the son of God truly recognize him as such, and nevertheless the evangelist uses this fact as a counterpoint to those who recognize his true dignity.

The third evangelist, in turn, emphasizes Jesus’ relationship with the Father, framed within an environment of prayer, intimacy and trust, of self-giving and submission, right up to the last words pronounced on the Cross: Father, into your hands I commend my spirit. [15]

At the same time, it is easy to capture how Jesus’ life and mission are continually guided by the Holy Spirit, right from the Annunciation when his divine filiation is proclaimed. Together with these features especially highlighted by St. Luke, we find other testimonies common to the other evangelists: the evil spirits call Jesus “Son of God” in the temptations in the desert and in the cures of the possessed people in Capharnaum and in Gerasa.

In St. John, Christ’s divine filiation is presented with its most profound and transcendent meaning. He is the Word, who is in God’s bosom and who takes on our flesh. He is pre-existent, existing before Abraham. He was sent by the Father, and has come down from heaven…. These characteristics highlight the reality of Jesus’ divinity. The confession of his divinity by Thomas can be seen as the culmination of this Gospel, which was written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that believing you may have life in his name.[16]

In St. John, perhaps more than in any other Gospel, the affirmation of Jesus’ real divinity clearly forms part of the very core of the apostolic preaching. Moreover, this affirmation is grounded in the awareness Christ himself had during his time here on earth.

In this sense, it is of special interest to recall (and this is something all the Evangelists record) how Jesus distinguishes his relationship with the Father from other people’s:it is my Father who glorifies me, of whom you say that he is your God ;[17] I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.[18] The expression “our Father” appears on Jesus’ lips only on one occasion, when teaching the disciples how they are to pray. Christ never put his special filiation on the same level as that of his disciples. This is a sign of the awareness he himself had of his divinity.

The preaching of the early Christian community made use of proclamations, catechesis, exhortations and arguments in support of the faith, forms that are also present in the Gospel narrative. But this fact influenced its literary style rather than the actual events it records.

It is useful to realize that the demands of preaching meant selecting certain passages in preference to many others that could have been used, [19] and that it spurred the Evangelists to present the life of Christ in a way that was theological rather than biographical, thematic rather than chronological. But there is no reason to think that this led them to falsify recollections, to create or invent them.

Moreover, the inclusion of disconcerting expressions and events is another proof of the credibility of the Gospels. Why should Christ have been baptized if he had no sin? Why mention the apparent ignorance of Jesus with respect to the Parousia, or that he was unable at times to perform miracles, or that he was tired? Another sign of credibility is the Semitic form of the words, and the use of expressions that were archaic or not taken up by later theology, such as “son of Man.”

The Gospel narrative is filled with episodes that show candor and naturalness. These are a sign of its veracity, and of the desire to recount the life of Jesus within the setting of the Church’s tradition. Whoever listens to and receives the Word can become a disciple. [20]

In the Christian message, faith and history, theology and reason are intertwined, and the apostolic witnesses show a determination to base their faith and message on facts, told with sincerity. In the Gospel pages, Christ makes himself known to men of all times, in the reality of his life, of his message. In reading them, we are presented with much more than just a moral ideal or doctrine. We are led to “meditate on the life of Jesus, from his birth in a stable right up to his death and resurrection,” [21] because “when you love someone, you want to know all about his life and character, so as to become like him.” [22]

B. Estrada

Footnotes

[1] Cf. Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth , ch. 1 and 2.

[2] Saint Josemaria Escriva, The Way, no. 584.

[4] Cf. Flavius Josephus, Antiquitates Judaicae 18, 3, 3.

[5] Vatican II, Dogmatic Const. Dei Verbum ,no. 18.

[6] Cf. Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth , Foreword, p. xxiii.

[9] Catechism of the Catholic Church, no. 515.

[10] Saint Josemaria Escriva, Friends of God, no. 216.

[20] Cf. Joseph Ratzinger (Benedict XVI), Jesus of Nazareth ,Chapter 4, p. 117.

[21] Saint Josemaria Escriva, Christ Is Passing By, no. 107.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.