Christians formed local communities – churches – under the pastoral authority of a bishop. The bishop of Rome – the successor of the Apostle Peter – exercised a primacy over all the churches. The Eucharist was the center of Christian life. The rejection of Gnosticism was the major doctrinal achievement of the early Church.

1. Introduction

In its expansion in the ancient world Christianity adapted itself to the institutions and lifestyle of Roman society. We have already seen how the principle of Christian universalism became more and more patent; we have also looked at the relationships between Church and the pagan empire. Now we will study the main features of life inside the Christian communities: their hierarchical and social make-up, pastoral government, discipline, liturgy, etc.

Wherever it went, classical Rome, by policy, promoted city life: municipalities and colonies developed over all the provinces of an empire in which urbanization meant Romanization. Christianity was born in this historical context, and it was in the cities that the first Christian communities established themselves, as local churches. Their surroundings were pagan and hostile – which had the effect of giving them greater internal cohesion and made for solidarity among their members. Yet these churches were not isolated nuclei: there was a real communion and communication among the churches and they all had a keen sense of being components of one and the same world-wide Church, the one and only Church founded by Jesus Christ.

2. Hierarchy of the Early Church

Many of the churches of the first century were founded by Apostles, and as long as these Apostles lived they remained under their authority, being managed by a ‘college’ of priests who were in charge of their liturgical life and their good order. This system of government can be seen especially in the Pauline churches founded by the Apostle of the Gentiles. But as the Apostles died monarchical local episcopacy – which had been introduced from the very beginning in some churches – became the general system. The bishop was the head of the church, the shepherd of the faithful, and as successor of the Apostles, he had the fullness of the priesthood and the authority necessary for governing the community.

The key to the unity of the churches scattered throughout the world, which together made up one, universal Church, was the institution of the Roman primacy. Christ, the founder of the Church – as was pointed out elsewhere – chose the Apostle Peter as the firm rock on which to base his Church. But the primacy conferred by Christ on Peter was in no way a temporary, circumstantial affair, fated to disappear when Peter died. It was a permanent institution, an earnest of the permanence of the Church, something that would be valid for all times.

Peter was the first bishop of Rome, and his successor in the see of Rome also succeeded to the prerogative of the primacy, which conferred on the Church the monarchical constitution which Jesus Christ wised it to have always. The Roman church was therefore – and for all times – the center of unity of the universal Church.

3. The Exercise of the Primacy

The way in which the primacy is exercised has naturally been conditioned, over the centuries, by historical circumstances. In periods of persecution or when communication was difficult, the exercise of the primacy was less easy, less intense, than when times were better. But history allows us to document, from the very beginning, both the local churches’ recognition of the pre-eminence of the Roman church and also the consciousness the bishops of Rome had of their primacy over the universal Church.

At the beginning of the second century, St. Ignatius, bishop of Antioch, wrote that the Roman church was the church ‘placed at the head of charity,’ thereby attributing to it a right of supremacy over the whole Church. For St. Irenaeus of Lyons in his treatise Against Heresies(c. 185), the church of Rome enjoyed a singular pre-eminence and was the touchstone for judging what the true teaching of the faith was.

In the fist century, we can find an outstanding indication of how aware bishops were of their primacy. In connection with a serious internal problem in the church of Corinth, Pope Clement Iintervened with authority: his letter, laying down the procedure to be followed and requiring obedience of his instructions, is a clear proof of how aware he was of his primatial authority; no less significant is the respectful and docile acceptance given to the pope’s intervention by the church of Corinth.

4. Process of conversion

“Christians are not born, they are made,” wrote Tertullian towards the end of the second century. These words may mean, among other things, that at that time the great majority of the faithful were not – as would be the case from the fourth century onwards – children of Christian parents, but rather people who had been Gentiles originally and had come to the Church by being converted to the faith of Jesus Christ. Baptism – the sacrament of incorporation into the Church – was at that time the last stage in a slow process of Christian initiation.

This process, beginning with the conversion, developed through a long ‘catechumenate’, a testing-time and a period of catechetical instruction, which was the established procedure from the end of the second century. The liturgical life of Christians centered on theEucharistic sacrifice, which was offered at least every Lord’s day, whether in a Christian household – the seat of some ‘domestic church’ – or in places set aside for worship, which began to exist from the third century.

5. The cultural diversity among the Christians

The early Christian communities were made up of all sorts of people, without any class or other kind of distinction. From Apostolic times, the Church was open to Jews and Gentiles, rich and poor, free men and slaves. Nevertheless it is true that most Christians were people of humble condition. Celsus, a pagan intellectual hostile to Christianity, mocked at the weavers, shoemakers, washermen, and other uneducated types who were spreading the Gospel in every sector of society.

But it is an undoubted fact that even early on some members of the Roman aristocracy embraced Christianity: so much so, that one of Emperor Valerian’s persecution edicts was specially directed against the senators, gentlemen and imperial officials who were Christians.

6. Structure of the early Christian communities

The internal structure of the Christian communities washierarchical. The bishop – the head of the local church – was assisted by clergy, whose higher ranks – the order of priests and the order of deacons – were, like the episcopacy, of divine institution. Lesser clergy, who were assigned the particular ecclesiastical functions, appeared in the course of the centuries. The faithful who made up the people of God were, in their immense majority, ordinary Christians, but there were distinctions among these also.

In the Apostolic age, there were numerous charismatics – Christians who received exceptional gifts of the Holy Spirit with which to serve the Church. Charismatics played an important role in the primitive Church, but they were a passing phenomenon which practically disappeared in the first century of the Christian era. Throughout the period of the persecutions, the ‘confessors of the faith’ enjoyed special prestige: these were so-called because they had ‘confessed’ their faith as the martyrs had, but had survived imprisonment and torture.

And there were Christian faithful whose life or ministries gave them a special status – the widows, who from Apostolic times formed an ‘order’ and looked after ministries to do with women; and the ascetics and the virgins, who embraced celibacy ‘for the love of the kingdom of heaven’ and constituted, as St. Cyprian put it, ‘the most heavenly portion of Christ’s flock.

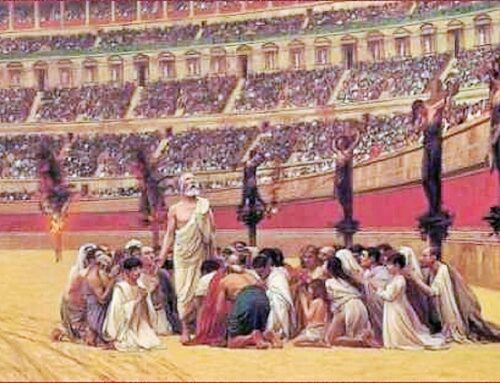

7. Vindication of primitive Christianity

The first Christians suffered the severe external test ofpersecution; internally, the Church had to face no less a test – the defense of the truth against contemporary ideologies which sought to undermine the basic dogmas of the Christian faith. The early heresies – this was the name given to these currents of ideas – can be divided into three groups. There was an heretical Judaeo-Christianity, which denied the divinity of Jesus Christ and the redemptive effectiveness of his death: the messianic mission of Jesus, according to them, consisted in bringing Judaism to perfection by complete observance of the Mosaic law. A second group of heresies – which appeared

later – was characterized by moral rigorism, fed by belief that the end of the world was at hand. In the second century, the best-known of these heresies was Montanism, although in Roman Africa at the beginning of the fourth century, extreme rigorism was also one of the features of Donatism.

But the greatest internal heresy the Church had to face during the age of the martyrs was, without doubt, Gnosticism. Gnosticism was a great ideological current tending towards that religious syncretism which was so fashionable during the last centuries of antiquity.Gnosticism – which was a real school of thought – claimed to be a higher wisdom accessible only to minority elites of initiates. Its policy towards Christianity was to distort the truths of faith by presenting gnostic teaching as the genuine expression of the most sublime Christian tradition – that teaching which Christ had given only to his most intimate disciples, those ‘capable of understanding’ what must remain hidden to the common run of faithful. The most notable exponent of Gnosticism was Marcion, who founded a pseudochurch which tried to imitate the Christian Church’s structure and liturgy. The Church reacted energetically against Gnostic infiltration of the Christian communities, while its theologians demonstrated the doctrinal incompatibility of Christianity and Gnosticism.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.